Is treasure actually a thing in India? That entirely depends on who you ask.

If one were to rely exclusively on Western academic publications, one might easily conclude that treasure is not really a thing in India, and never has been. A search of the website academia.edu will throw up zero academic titles containing the Indian word for treasure, nidhi, and barely one or two papers containing the term anywhere in the body of their text. In similar vein, there is only one full academic article devoted to the Indian Lord of Treasures, Kubera, and none at all to his famous Nine Treasures.

According to Indians however, nidhi is a very big thing indeed within their culture, and always has been. Various Google searches for the ubiquitous ‘Nine Nidhis’ of Indian thought throw up 1,020,000 results for ‘nava nidhis’, 587,000 results for the more Sikh-friendly ‘nau nidh’, and even 196,000 results for the English search term ‘nine treasures of Kubera’, almost all of the latter from English-language Indian websites. Kubera himself throws up 18,300,000 search results, although many of these are for his namesakes, be they financial advisers, crypto currency dealers, fintech programs, or even video games.

Numerous popular religious blogs and websites expound the topic of the nine nidhis, be they Sikh or ISKCON, modern New Age or conservative Vedic, be they Vaiṣṇava or Śaiva, focused on Hanuman or Gaṇeśa, North Indian or South Indian. I have no idea how many hits might turn up if one searched in Hindi or Tamil rather than in English. But I doubt there are very many people alive in India today who are not in some way or another familiar with Kubera, the King of the Yakṣas, and his Nine Treasures.

Anecdotal evidence reinforces the paradox. In the course of my own conversations and correspondences, I have found surprisingly few contemporary Western academic Indologists with much inkling of what the ancient and extraordinarily convoluted and multivalent term nidhi refers to. Things might have been different in the past, since Vogel (1926) did devote some thought to nidhi in the course of his classic study of nāgas, and K. R. Norman (1992) and Nalini Balbir (1993) subsequently wrote articles on important aspects of the subject. Yet even these worthy efforts of the last century hardly reflect the ubiquity of the topic within Indian religious and non religious writing alike.

The Sikh scripture, the Guru Granth Sahib, has more than a hundred references to the Nine Nidhis, many attributed to the first of their ten gurus, Nānak (1469 -1539). Little wonder that the topic is so ubiquitous in modern Sikhism. K. R. Norman (1992: 185, note 12) has observed that the nine-fold nidhi was so well known and pervasive a category in India that the word nidhi is even found in inscriptions simply to indicate the numeral ‘9’. Important Purāṇas such as the Garuḍa (Chapter 53), and the Mārkaṇḍeya (Chapter 68), have entire chapters expounding a slightly different enumeration of eight nidhis: no wonder the topic is widely discussed in Hindu circles. There is even a famous myth underpinning the fabulous wealth of the richest and most visited temple in the world, the Venkateswara Temple in Tirumala, describing Venkateswara Balaji’s eternal indebtedness to Kubera after he took a loan to pay for his wedding. This extremely well known myth invokes the idea of Kubera as lord of nidhi.

In the course of her description of the Indian art of treasure finding (nidhivāda), and its intimate interelation and overlap with mineralogy (khanyavāda) and alchemy (rasavāda), Nalini Balbir has remarked how Indian literary narratives are full of references to nidhi. Her paper is only a first introduction this very broad topic, and was largely derived from those literary and Jain narrative texts that comprise her special areas of academic focus, but even without paying much attention beyond these confines, she cited references to nidhi from at least thirty different and mainly non-religious narrative works, most of which I list below (see Appendix 2).

K. R. Norman inter alia introduces the nidhis in Indian lexicographical texts, such as Amarasiṃha’s famous Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana lexicon, usually known as the Amarakoṣa or Amarakośa, and Hemacandra’s Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacaritra. Following Vogel, Norman also discussed the occurrences of the term nidhi in Indian Buddhist literature, where it displays a distinctive four-fold enumeration, including in such varied texts as the Divyāvadāna (which parallels the Mūlasarvastivādin vinaya), the Mahāvastu, the Khotanese Book of Zambasta, the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa, the Maitreyavyākaraṇa, and the Karmaśataka. The Pāli commentaries (Nidānakathā) in particular make much of these four nidhi, identifying them as one of the seven co-natals (saha-jāta) that appear spontaneously whenever a Buddha is born.

In the context of numerous narratives of nāgas controlling treasures both sacred and mundane, notably in early Buddhism, and their control over local agricultural economies, Vogel (1926: 210-11) also discusses the Four Great Nidhis (chatur-mahānidhi-sthāḥ) of early Indian Buddhist literature, and their connection with famous nāga kings dwelling at specific geographical locations. Vogel mentions the eye-witness reports of the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, whose observations he believes are consistent with the cult of these four great nidhi-owning Buddhist nāgas.

It is with these observations that we finally arrive at my real point, which is a Tibetological one. Even if we, as western academics, are content to remain largely unaware of what the multivalent Indian term nidhi refers to, Tibetan translators and scholars of the early translation period were not like us. They were more like Indians. They understood the term nidhi was important in Indian culture, and they necessarily sought to understand it in the same way that Indians understood it. True, in the course of time Tibetan civilisation came to rather magnificently stretch the range of the word, but nevertheless, the starting point was without doubt a close reading of the Indian meanings of the term nidhi.

The term that Tibetans consistently and invariably used to translate the Indian term nidhi, was the Tibetan root gter. We find this rendering demonstrated not only in the Mahāvyutpatti, but also in translations of many Sanskrit tantras such as the Amoghapāśakalparāja (listed in the lHan dkar ma, number 316), in translations of Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa, and in translations of seminal Sanskrit lexicons such as the Amarakośa. Wherever the Sanskrit versions of these texts, and many others like them, have nidhi, the Tibetan translations have gter.

Unlike us modern academics however, the translators of the early period of translation (snga dar) could not so easily enjoy the luxury of turning a blind eye to the complex meanings of this conceptually difficult term. For example, a single Kriyātantra that is cited in the lHan dkar ma (number 317) the Vidyottamamahātantra, has at least 60 occurences, some of them embedded within lengthy passages focused specifically on the topic of nidhi. Unlike us, the translators could have had no escape. They simply had to get to grips with the meanings of nidhi, however complex. Based on the surviving textual and linguistic evidence from all known sources, Joanna Bialek has tentatively proposed a hypothesis, that the Tibetan word gter might have been a translational neologism, purposely coined to render the Indian word nidhi.

Nalini Balbir has already pointed to the sensitivity of the compilers of the Mahāvyutpatti in including the mineralogical nuances of this complex term, thus showing how they seemed to understand the intimate interrelation in India between the arts of nidhivāda (treasure finding) and khanyavāda (mineralogy) (Balbir 1993: 20).

But to my current knowledge, it is surely Guru Chos dbang in his gTer ‘byung chen mo who demonstrates the most virtuosic and complete philosophical understanding of the complex Indian concept. He must really have considered the issues with great thorougness, with all the instincts of a natural anthropologist. I am not sure what Chos dbang’s sources were. Certainly he follows time-honoured Indian Buddhist conventions in presenting a basically four-fold outer structure. But much more than that, he undoubtedly understands the full complexity of nidhi as an Indian term that operates simultaneously on so many quite different yet deeply interelated dimensions. My present supposition is that his task was made easier, by the prior existence of an indigenous Tibetan theory of environment, economy, wealth, and value, that already ran closely parallel to the Indian one.

Be that as it may, Chos dbang quite impressively understood all of the following about Indian nidhi:

- that nidhi entailed a specific understanding of the geographical environment and landscape, and the powerful non-human inhabitants dwelling therein

- that nidhi is particularly connected with nāga territorial deities

- that nidhi is likewise connected with yakṣa territorial deities

- that nidhi supplies a general explanation of mundane economic wealth, as well as a theory of value

- that nidhi need not be hidden by any agent, but can be naturally present

- that nidhi can also be hidden by specific agents, both human and non-human

- that the discovery of nidhi requires very precise ritual performances

- that the territorial deity guardians of nidhi are potentially dangerous and must be placated

- that the territorial deity guardians of nidhi are potentially convertable into Buddhist protectors

- that the category of nidhi has age-old associations with the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Saṅgha, in the literatures of all three vehicles of Śrāvakayāna, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna.

- that nidhi has a long association with the revelation of previously hidden scriptural texts

- that nidhi is specified by name as a component part of the classic Indian Mahāyāna narrative of dharmabhāṇakas reincarnating to find scriptures originally entrusted to them by the Buddha

- that nidhi can also have many important abstract spiritual meanings

- Chos dbang also manages to include within his classifications of gter, pretty much all the varied categories of nidhi listed in such standard Indian texts as Amarasiṃha’s Amarakośa and Hemacandra’s Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacaritra. These include such things as jewels, foods, military items, clothes, grains and crops, new locations for human settlement, mines, all the various arts and crafts and sciences, ornaments for both humans and animals, offspring, all kinds of wealth, knowledge of calculations and measurements, occult knowledge, the dramatic arts, and so on and so forth (see Appendix 1 below).

Janet Gyatso (1994) was the first Western academic scholar to look at Guru Chos dbang’s gTer ‘byung chen mo, closely followed by Ronald Davidson, who went on to examine Ratna Gling pa’s work on the same topic. Gyatso’s article is an exceptional peice of scholarship, to which I constantly return for inspiration, and which deservedly remains a classic of Tibetological writing. Yet for her, for Davidson, and for almost all other Western academic scholars of their generation, nidhi was simply not a thing. Even if the term nidhi might have been encountered here or there, it did not exist as a significant category within Indian culture. Like Schrödinger’s cat, nidhi simultaneously existed in India, while not existing in the West. Hence neither Gyatso nor Davidson could recognise that Guru Chos dbang was so thoughtfully producing his own account of nidhi in his gTer ‘byung chen mo. Instead of recognising that he was grappling with the idea of nidhi, Gyatso simply wrote: “We almost begin to suspect that Guru Chos-dbang is going to argue that everything is a kind of Treasure” (Gyatso 1994:276). What Chos dbang was actually doing was something rather more particular and more nuanced: following Indian lexicographical definitions, he was arguing that anything of intrinsic value, be it spiritual or mundane, which was once hidden and later revealed, could count as gter. And gter is the Tibetan translation of nidhi.

For a more extensive discussion of these issues, see Mayer 2022.

Appendix 1 Some samples of Indian classifications of nidhi.

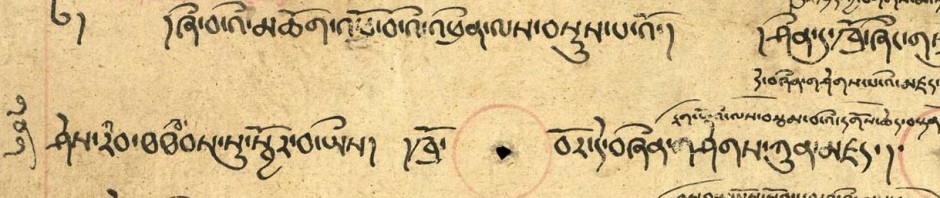

Hemacandra’s (1088-1173) list of the Nine Nidhis below is taken from his Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacaritra and is based on a canonical Jain text, the Ṭhāṇaṃga-sutta. Note that his famous lexicon or dictionary of synonyms, the Abhidhānacintāmaṇi, also has a further entry for nidhi.

[1] the nidhi Naiṣarpa is the origin of the building of camps, cities, villages, mines, towns approached by land or sea, and isolated towns; [2] the nidhi Pāṇḍuka is the origin of all bulk, weight, and height, and of all numbers, and of grains and seeds; [3] the nidhi Piṅgala is the origin of the whole business of ornaments, for both humans and animals; [4] the nidhi Sarvaratna is the origin of the Cakravartin’s jewels; [5] the nidhi Mahāpadma is the origin of all clothing; [6] the nidhi Kāla is the origin of knowledge of the past, present and future, also of labour such as agriculture, and the arts [7] the nidhi Mahākāla is the origin of coral, silver, gold, pearls, iron, etc. and their mines; [8] the nidhi Māṇava is the origin of soldiers, weapons, armour, the sciences of fighting, and the administration of justice; [9] the nidhi Śaṅkha is the origin of poetry, concerts, dramatic arts, and musical instruments.

Amarasiṃha’s list of the Nine Nidhis from his Amarakośa are particularly famous, but here only their proper names are given: [1] Padma (Lotus), [2] Mahāpadma (Great Lotus), [3] Śaṅkha (Conch), [4] Makara (Crocodile), [5] Kacchapa (Tortoise), [6] Mukunda (a gemstone?), [7] Kunda (Jasmine), [8] Nīla (Sapphire), and [9] Kharva (Dwarf). There are many different ways of interpreting these names. As one example among hundreds, a Sikh analysis of the famous Amarakośa list is that, from a worldly point of view, they signify in order (1) offspring, (2) jewels, (3) foods, (4) military prowess, (5) clothes and grains, (6) gold, (7) successful trade in gems, (8) arts, and (9) riches of all kinds; while their spiritual aspects are (1) faith, (2) devotion, (3) contentment, (4) detachment, (5) acceptance, (6) equipoise, (7) delight, (8) joy, and (9) awakening.

The above lists give an indicative but not even remotely complete view of some of the multifarious Indian understandings of the Nine nidhi. There are also Purāṇic lists of Eight Nidhis, and many more variations besides.

Appendix 2: some of the Indian narrative texts describing nidhi cited in Nalini Balbir (1993)

Harṣacarita of Bāṇa (mid-6th century) in several places.

Kathāsagitsāgara 7.1.37ff sqq. (Ocean III, p.157-158); 43.37sqq. (Ocean II, p.159-160);

Pañcatantra 1.20 (Duṣtabuddhi and Pāpabuddhi), V.3 (siddhi-varti),

Kathāratnākara of Hemavijaya

Daśakumāracarita of Daṇḍin

Samarāiccakahā, a novel by Haribhadra (8th century)

Pradyumnasūri (13th century

Upadeśapada in Haribhadra’s version

Āvaśyaka IX.58.5 (cūrṇi 553.10-11; ṭīkā of Haribhadra [Āvaśyaka-sūtra, a Śvetāmbara canonical scripture?

Upadeśapada [a Jain narrative collection] which gravitates in the orbit of the āvaśyakean literature.

Bṛhatsaṃhitā by Varāhamihira

Gargasaṃhitā

Udayasundārikathā 21.23

Yaśastilakacampū of Somadevasūri (11th century)

Campūrāmāyaṇa

Prabandhakośa 28.7

Prabhāvakacarita 82.5

Vividhatīrthakalpa

Siṃhasūri’s (6th century?), commentary on the Dvādaśāra-nayacakra, an important philosophical work by the Jaïna Malavādin (4th century?):

Kuvalayamālā of Uddyotanasūrī (completed in 779; 104.21sqq)

abridged Sanskrit by Ratnaprabhasūri (13th century; *46.1sqq)

Upamitibhavaprapañca Kathā of Siddharṣi (completed in 805; 865.7sqq)

Puhaicandacariya of Śāntisūri (completed in 1105; 119.23sqq)

Ākhyānakamaṇikośavṛtti of Āmradeva (12th century; 137.6 sqq)

Maṇoramākahā of Vardhamānasūri (12th century; 114.13sqq)

Līlāvatīsāra of Jinaratna (13th century) 6.182sqq and 391sqq)

Nidhipradīpikā which brings together chapters 20 and 21 of the Kakṣapuṭa or Siddhanāgārjunatantra, attributed to Nāgārjuna the alchemist

A further Nidhipradīpikā in twenty-eight chapters, taken from the Siddhaśābaratantra

Nidhipradīpa by Śrīkaṇṭhasámbhu

Kakṣaputa

Rasendracūḍāmaṇi (12th century; 3.29cd)

Bibliography:

Balbir, Nalini, 1993. “À la recherche des trésors souterrains“, in Studies in honour of Gerrit Jan Meulenbeld: Journal of the European Āyurvedic Society vol. 3, 1993, pp. 15– 55.

Guru Chos dbang, n.d. gTer ‘byung chen mo, pages 75-193, within Gu ru chos dbang gi rnam dang zhal gdams, Rin chen gter mdzod chen po’i rgyab chos Vols 8-9, Ugyen Tempa’i Gyaltsen, Paro, 1979. TBRC Work Number 23802.

Gyatso, Janet, 1994. “Guru Chos dbang’s gTer ‘byung chen mo: an early survey of the treasure tradition and its strategies in discussing Bon treasure”, PIATS 6, vol. 1, Oslo, Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, 1994, pp. 275-287.

Mayer, Rob, 2022. “Indian nidhi, Tibetan gter ma, Guru Chos dbang, and a Kriyātantra on Treasure Doors: Rethinking Treasure (part two)”, in Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, no. 64, Juiller 2022, pp. 368-446.

Norman, K. Roy, 1992 “The Nine Treasures of a Cakravartin”, in Collected Papers, vol. 3, Oxford, The Pali Text Society, 1992, pp. 183-193.

Vogel, Jean Ph. , 1926 Indian Serpent Lore or the Nāgas in Hindu Legend and Art, London, Arthur Probsthain, 1926.