When did the figure of Padmasambhava first become mythologised, when did he first become incorporated into ritual, when did his apotheosis begin?

For Tibetan tradition, the answers are simple. Padmasambhava was a peerless guru with the vidyādhara’s control over lifespan, who became revered in Tibet when Emperor Trisongdetsen invited him, by which time he had already been a living legend in India for many centuries.

Modern academics are denied such beautiful and easy answers. In general we are permitted to accept as valid evidence far less data than traditional Tibetan historians, and in few places is this felt more acutely than the history of Padmasambhava: for modern scholarship, the admissible historical evidence for the person or even for his representation is very slight indeed.

Following the digitisation of the Dunhuang texts over the last decade, we have happily seen a small augmentation of the available evidence for the early representations of the great Guru, even if not for the great Guru himself. Part of that augmentation has come from the discovery of a new Dunhuang source, and part from a more intensive analysis of already known sources. However, Cathy and I are not convinced that the implications of the new source have so far been fully appreciated, nor that the bigger picture as it should now stand has been properly assessed. In this multi-part blog I want to present a more thorough interrogation of the new source of evidence, together with a fuller investigation of the already known sources, to arrive at a more complete depiction of what we can now know about the prehistory of Padmasambhava’s early representation if we put all the available evidence together.

The most convenient summary of how the historical Padmasambhava looked to modern scholarship before the digitisation of the Dunhuang texts comes from Matthew Kapstein. Writing in 2000, the only admissible evidence then available to him was fourfold:

(i) The early historical text, the Testament of Ba, which presents Padmasambhava visiting Tibet.

(ii) The 10th century Dunhuang text PT44, which narrates Padmasambhava bringing the Vajrakīla tradition to Tibet.

(iii) An early text attributed to Padmasambhava called the Garland of Views, or man ngag lta ‘phreng, and a commentary on it by the 11th century rNying ma sage, Rong zom

(iv) The termas of Nyang ral (1124-1192) and Guru Chowang (1212-1270), which present fully-fledged apotheoses of Padmasambhava as a fully-enlightened Buddha.

Based on this evidence, Matthew Kapstein concluded that:

(i) The Testament of Ba shows Padmasambhava quite likely did visit Tibet during Trisongdetsen’s reign.

(ii) PT44 indicates followers of his tantric teachings were active in post-Imperial Tibet.

(iii) Rong zom’s commentary and the few Dunhuang references show that the Padmasambhava cult began its ascent during the ‘time of fragments’, between the end of Empire and the start of the gsar ma period in the late 10th century.

(iv) Nyang ral and Chowang’s termas suggest the most massive elaboration of Padmasambhava’s cult developed from the 12th century.[1]

Since Matthew Kapstein published that in 2000, there have been two further developments. Firstly, a new Dunhuang source, PT307, was felicitously discovered by Jacob Dalton, who published an article on it (this article also deals with another Dunhung text, TibJ644, that Jake Dalton had initially hoped related to Padmasambhava, but after some last-minute discussions between us, we decided was not yet so conclusively established as initially hoped).[2]

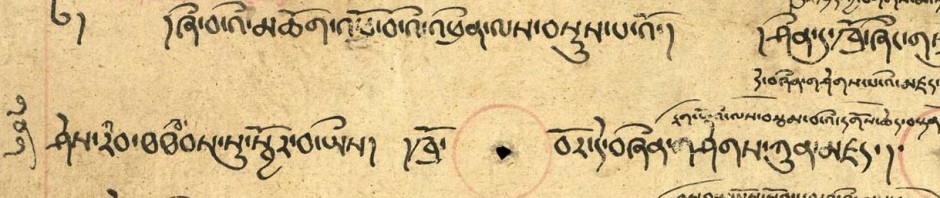

Secondly, Cathy and I are completing a much more detailed analysis than has hitherto been attempted of the evidence from the Dunhuang text IOL Tib J 321, looking at it more carefully than Ken Eastman’s short note from the 1980’s, Jake Dalton brief survey in 2004/6?, or Sam van Schaik’s small blog entry in 2007. It is largely these two sources of evidence that will inform my paper today, together with a reassessment of the already well-known sources PT 44 and the Testament of Ba.

So what can the new and fully admissible evidence tell us different from what Matthew Kapstein wrote in 2000? It is a tribute to his historical discipline, and the caution with which his reasoning neither exceeded nor underrated the scanty evidence, that the advances we can now report consist more of detail than of substance. Kapstein wisely put no definite dates on any particular aspect of the Padmasambhava cult, which he understood as a gradual process developing throughout the post-imperial period, coming to some sort of culmination with Nyang ral three centuries later. What is new is that we now have much stronger evidence that the mythologisation of Padmasambhava, his incorporation into ritual, and it seems even his apotheosis, began within the earlier part of the very long time frame Matthew Kapstein suggested. In other words, when portraying Padmasambhava in his famous hagiographical and historical writings, Nyang ral was developing existent themes, rather than inventing new ones. Our new evidence suggests that Padmasambhava was already the object of religious myth and ritual worship, and was probably already seen as the enlightened source of tantric scriptures, as many as two hundred years before Nyang ral, even if not yet with so much poetic elaboration. An important proviso is that we have not yet ascertained if the evidence bears witness to a widespread veneration of Padma in the tenth century, or something narrower followed only by a few. This is because the evidence currently available suggests two different views of Padma in the early sources:

- Firstly, in the context of the possibly early or mid 10th century rDzogs chen oriented bSam gtan mig sgron of gNubs sangs rgyas ye shes, he is cited as a great teacher and even mythologised, but no more so than his peers like Vimalamitra, and there is no sign of his integration into ritual (but of course, we cannot yet tell for sure if the sole available version of this text includes later interpolations or not).

- Secondly, in the possibly late 10th century Mahāyoga texts from Dunhuang, he is mythologised, incorporated into ritual, and elevated above his peers, even apotheosized. The available versions of the testament of Ba seem to broadly concur with this.

Jake Dalton has in the last five years or so emerged as one of the most frequently cited interpreters of the early rNying ma pa, and is widely renowned as a highly innovative and interesting scholar. He has recognised, as many others such as Anne-Marie Blondeau and Matthew Kapstein did before him, that there is real evidence for some kind of a Padmasambhava cult from the 10th century or earlier. However, we think his work in this particular instance has not yet exhausted the possibilities for these sources, despite his early access to them. This is because Jake has not focused enough on the ritual function of the Dunhaung texts related to Padmasambhava, nor their connections with Mahāyoga; approaching them mainly in terms of their narratives divorced from ritual context, he has several times arrived at incomplete or even slightly inaccurate conclusions. By not recognising the ritual clues, he has significantly underestimated the full import of these extraordinary sources whose evidence for the early Padmasambhava cult is in fact quite a lot richer than he realises.

I was impressed to see on a YouTube interview made on his campus that Paul Harrison of Stanford University, although not a practising Buddhist, has learned the Diamond Sūtra by heart and recites it daily, to introduce a performative understanding into his academic research on this text. In the same way, academic scholars of tantrism might benefit sometimes by actually performing tantric rituals themselves, to get a more nuanced view of things.

In the subsequent parts of this blog, I will set out in detail the further insights we can add to Jake Dalton’s, and indeed Matthew Kapstein’s and various other scholars’ earlier findings, by approaching the Dunhuang evidence for Padmasambhava through the lens of ritual. After all, it has never been doubted that PT44 and PT307 must be connected in some way with ritual. No one has ever suggested otherwise, because both comprise stilted narratives culminating in explicitly ritual passages. The reason they have not so far been studied through the lens of ritual is probably one of methodological tradition: in the short history of their subject, unlike the anthropologists, academic tantric textual scholars have quite simply never been expected to approach their materials from a performative perspective. I wonder if it might be time for that to change.

[1] Matthew Kapstein, 2000. The Tibetan Assimilation of Buddhism. New York, Oxford University Press. See pages 155-160.

[2] TibJ644 does not anywhere mention Padmasambhava by name, and we still need to clarify if the description it gives is simply a generic peice of Kriyātantra writing. See my article in the Journal of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, ‘The Importance of the Underworlds: Asura’s caves in Buddhism and Some Other Themes in Early Buddhist Tantras Reminiscent of the Later Padmasambhava Legends’, http://www.thlib.org/collections/texts/jiats/#jiats=/03/mayer/

8 Responses to Padmasambhava in early Tibetan myth and ritual: Part 1, Introduction.