Tibetans, especially Nyingmapas, recount numerous legends of ‘Hidden Lands’ (sbas yul). These are places of refuge where the Dharma can be safeguarded in times of political danger and religious persecution, when temples are vandalised and religious books burned. Such ‘Hidden Lands’ are often characterised as obscure valleys in the remote Himalayas to the south of Tibet.

Although remote enough, Himalayan, and to the south, I can see why the Orgyan Ling temple in the Mon Tawang region in modern day Arunachal Pradesh might not have any such legends attached to it. It was not nearly obscure enough, and it ended up being sacked by a hostile army, with its many Nyingmapa treasures destroyed or carried away. Yet despite this rather serious setback, I would like to suggest that albeit in a rather tortuous way and perhaps inadvertently, it did nevertheless achieve one of the prime purposes ascribed to a ‘Hidden Land’. My reasons for proposing this have nothing to do with mystical revelations from Guru Rinpoche nor signs from the dakinis, but derive instead from the prosaic practice of philology. Orgyan Ling temple succeeded in preserving intact for posterity an important and famous Nyingma tantra in a considerably purer and more complete form than anywhere else in Tibet. Not only that, but it also preserved a number of other very rare Nyingma tantras not so far found anywhere else in the Tibetan cultural world.

Orgyan Ling was founded in the late 15th century by Orgyan Zangpo, the younger brother of the famous Bhutanese terton Pema Lingpa (1450-1521). In 1683, Orgyan Ling subsequently became the birthplace of Orgyan Zangpo’s famous descendent, the Sixth Dalai Lama Tsangyang Gyamtso (1683-1706). Thus it was that in 1699, the Fifth Dalai Lama’s regent, the great Desi Sangye Gyatso, greatly extended Orgyan Ling’s buildings and commissioned new volumes for its library. So despite its remote situation at the very edge of the Tibetan cultural sphere, its galactic network of family and personal connections enabled Orgyan Ling’s library to acquire some very fine books indeed, including a copy of the Ancient Tantra Collection (rNying ma’i rgyud ‘bum), and two Kanjur manuscripts.

The older of the Kanjurs was made in silver and gold, and both Kanjurs contained a quota of sixty Nyingma tantras freely intermingled with their Sarma tantras. This number greatly exceeds the merely twenty-four squeezed into the carefully segregated doxographical ghetto that had been reserved for them by Situ Gewai Lodro (1309-1364) in his Tshalpa Kanjur catalogue. Yet the Thempangma Kanjur traditions don’t have any Nyingma Tantra section at all. Orgyan Ling was evidently such a Nyingma stronghold that even its Kanjurs unashamedly sported unusually large numbers of Nyingma tantras, unsegregated from the Sarma tantras. We can only dream about what its long lost Ancient Tantra Collection might once have contained.

But fame is a two-edged sword which can prove fatal to any Himalayan valley’s chances of successfully qualifying as a ‘Hidden Land’. Not content with merely deposing him in Lhasa, after his death Tsangyang Gyamtso’s Mongolian enemies extended their sectarian vendetta to his birthplace, sacking the monastery of Orgyan Ling around 1714 in the course of a campaign against Bhutan.

Fortunately however, a quantity of the monastery’s surviving valuable books and artifacts were transferred to the Geluk establishment of Ganden Namgyal Lhatse in Tawang, even though the gold and silver Kanjur was partially destroyed, and the Ancient Tantra Collection disappeared.

Among the volumes transferred to Ganden Namgyal Lhatse was the Kanjur manuscript commissioned by the Desi Sangye Gyatso in 1699, beautifully calligraphed by master scribes especially hired from the E region of Central Tibet. Fortunately, this Kanjur still survives, together with its full complement of sixty Nyingma tantras. But it is not its master calligraphy that concerns us (although that is certainly impressive), nor its fine thick paper: rather, it is the presumably lost exemplars from which the master scribe must have made his copy, and the textual traditions they represented.

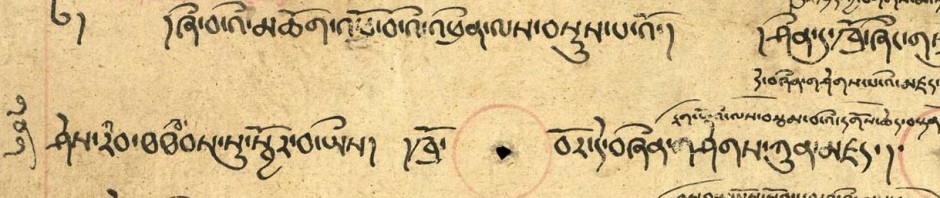

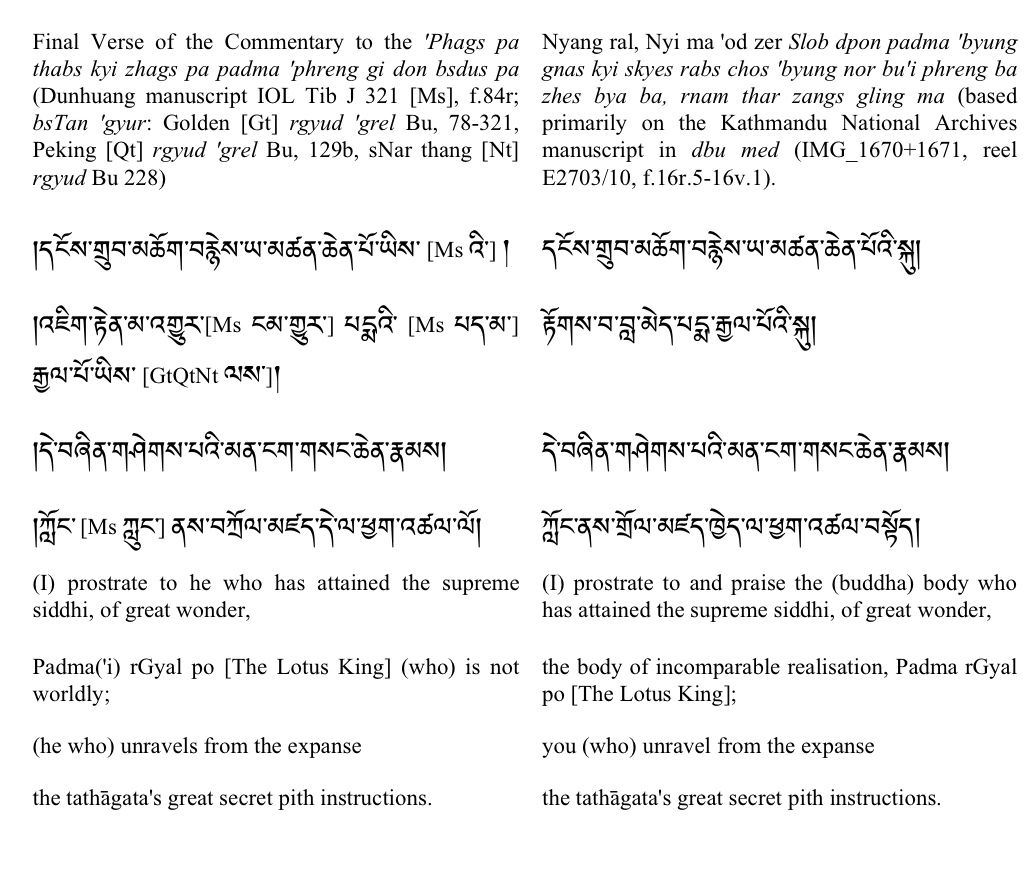

Over the last few years, Cathy and I have been engaged in making a critical edition of an important Nyingma tantra called the ‘Phags pa thabs kyi zhags pa padma ‘phreng gi don bsdus pa, which one might translate as A Noble Noose of Methods, the Lotus Garland Synopsis (hereafter abbreviated as Thabs zhags). In addition, we have simultaneously edited its commentary.

The Thabs zhags is a magnificent example of Mahāyoga literature, often juxtaposed with the Guhyagarbha in classic doxographies, and its commentary is one of the few remaining genuinely early word-for-word commentaries on a Mahāyoga tantra. While we don’t adhere to the unrealistically perfectionist dogma that every text in existence must be exhaustively critically edited as a matter of principle, as academic scholars we do share the perception of numerous learned Tibetan lamas of the past and the present, that a certain proportion of texts in the popular editions of the Tibetan canon can end up in rather bad shape, and are ideally in need of critical editing. It is specifically these damaged texts that we seek to restore.

The Thabs zhags and its commentary are among such damaged texts. The commentary survives in three different Tenjur editions, yet in all three instances, around a third of its text has become completely lost: for example, everything between Chapter Six and the end of Chapter 10 has disappeared, and there are other significant losses of text too.

In most of its more popular canonical versions, the root tantra has only slightly less serious problems. These more popular versions derive either from the Tshalpa branches of the Kanjur (which here must includes the Derge Ancient Tantra Collection, since it borrowed the relevant woodblocks from the Derge Kanjur), or from the Bhutanese Ancient Tantra Collection manuscripts. Yet they reveal a pattern of confusion: the respective renderings of the final section of the very long Chapter 11, for example, are so radically different in the Tshalpa Kanjur and Bhutanese recensions, that to the untrained eye it seems hard to credit that they are reproducing the same text at all.

To remedy this situation, we assembled twenty one different witnesses from every conceivable source, and began to try to piece together the evidence.

The commentary was reasonably easy to fix. Whilst the transmitted tradition of the Tenjur was irrevocably damaged, ‘new’ evidence in the form of a partially complete 10th century Dunhuang manuscript was discovered in the early 20th century and brought to London by Sir Aurel Stein. This enabled us to restore the text to its complete form, almost certainly for the first time in several centuries, since, by great good fortune, those parts missing in the Tenjur were preserved in the Dunhuang manuscript, while those parts missing in the Dunhuang manuscript were preserved in the Tenjur. It became a simple matter of splicing.

The root text proved more complex, but nevertheless exhaustive collation and stemmatic analysis permitted us a clear result. It became evident that the currently three most popular versions – those of the Tshalpa Kanjurs, of the Derge Ancient Tantra Collection, and of the Mtshams brag Ancient Tantra Collection from Bhutan – represented two distinct attempts to reconstruct the root text from out of the commentary. At some stage in its long history, the root text must have been lost in the main centres of Nyingma learning, perhaps during one of those periodic persecutions of the Nyingmapas that made them want to retire to the ‘Hidden Lands’ in the first place. Two different attempts were then made to recover the root text by extracting its verses out of the word-by-word commentary, one attempt witnessed in the Tshalpa Kanjurs and the Derge Ancient Tantra Collection, and the other attempt witnessed in the Bhutanese Ancient Tantra Collection manuscripts of Mtshams brag, Sgra med rtse, Sgang steng-A and Sgang steng-B.

Once we had the full commentary available to us together with the evidence from our twenty one witnesses, it became unfortunately evident that neither of these brave attempts at reconstruction had been entirely successful. Both in their different ways and at different junctures mistakenly introduced commentarial passages into the root text, whilst also excluding passages of root text through the mistaken assumption that they were commentary. Nor did they agree in their errors – hence for example their radically different interpretations of Chapter 11.

But this is where the ‘Hidden Land’ principle comes into play. While these famous mainstream texts of the Tshalpa Kanjur, the Derge Ancient Tantra Collection, and the Bhutanese Ancient Tantra Collection were uniformly confused about what was root text and what was commentary, all around that great geographical arc that comprises the southern Himalayan fringe of the Tibetan cultural zone, in sometimes obscure and ignored local monasteries, versions of the text survived that derived not from one or another attempt to reconstruct the root text from the commentary, but directly, from the original root text itself. In the forgotten ruins of an old library in Hemis, along the Nepalese borders, and even in far-off Bathang in the North-East of Tibet, ancient versions of the text, or their direct copies, survived. It was through studying these that we were able to restore the text to its original boundaries, differentiating root text from commentary with clarity and ease. Applying stemmatics to all the witnesses together, we were also able restore many other original readings.

But the last word belongs to the excellent Orgyan Ling manuscript. It can only be consulted in one place, in the library of the Central University for Tibetan Studies in Sarnath, and microfilm is not easily available. Hence we did not get to see it at all until a provisional version of our edition was already complete. To our delight and astonishment, it agreed with our stemmatic reconstruction at every significant juncture. Not only that, but its superior scribe from E had even eliminated spelling errors and many other small problems, just as our laborious edition had attempted to do. We found ourselves face to face with a beautifully calligraphed late 17th century version of the text that was virtually identical in all important respects to the one we had so painstakingly reconstructed over the previous three years. The only differences were that the Orgyan Ling manuscript preserved a few more archaic spellings than we saw fit, and its scribe had fallen for one minor slip of the pen when describing a mudra.

The moral of the story is this: we should not allow ourselves to become excessively swayed by the grand reputations and religious-political support invested in the few mainstream editions of the canons. Don’t forget the ‘Hidden Land’ principle, which tells us that just occasionally the most valuable editions can be located in the least expected places. This was something well understood by the great Tibetan critical editors of the past, men like Situ Panchen, Tsongkhapa or Kathok Rigdzin Tsewang Norbu, who became dissatisfied if they found reason to suspect that the standard canonical fare was deficient, and who left no stone unturned in seeking out rare witnesses in Sanskrit and Tibetan to complete their own critical editions.